Developing Strategy Under Uncertainty: Applying the Known-Unknown Matrix

How to use the Known-Unknown Matrix as a tool for starting a strategic process, organizing information, or dealing with decision block

Typically, at the heart of any strategy decision is a simple but difficult question that boils down to: "What should we do and why?" Answering this question is challenging—especially in a highly uncertain, dynamic, or ambiguous environment. One framework that has been utilized for decades by US intelligence agencies, the Department of Defense, and NASA to help answer this difficult question is the Known-Unknown Matrix.

This seemingly simple 2x2 matrix with Known and Unknown on each axis is not an end or a formulaic deliverable in strategic decision-making but a starting point. It's a tool for sharpening thinking by categorizing and defining a decision maker's knowledge about a given situation—helping separate fact from fiction and the concrete from the abstract.

The Known-Unknown Matrix became widely known through an infamous February 2002 press conference in which former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld explained his thinking as he evaded questions about the lack of evidence of the Iraqi government with the supply of weapons of mass destruction to terrorist groups. In his professional memoirs, aptly named Known and Unknown: A Memoir, Rumsfeld states that he first heard the Known-Unknown phrase from NASA director William Graham when they served together on the Commission to Assess the Ballistic Missile Threat in the late 1990s.

Breaking down the Known-Unknown Matrix

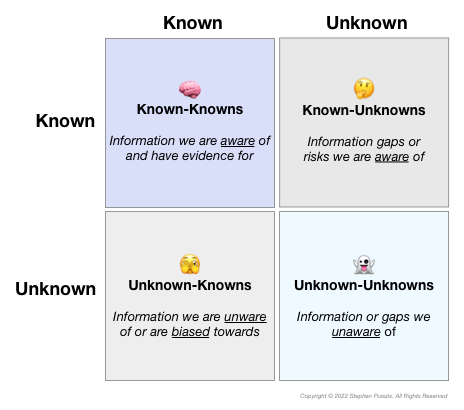

The Known-Unknown Matrix originates in the Johari Window, a psychological model to help individuals improve their self-awareness, also known as the feedback/disclosure model of self-awareness. The value of the Known-Unknown Matrix is the process by which a decision-maker defines and categorizes the relevant information to the problem or situation into four discrete categories:

- Known-Knowns: Information or knowledge that we are aware of and have evidence for.

- Known-Unknowns: Information/knowledge gaps or risks that we are aware of.

- Unknown-Knowns: Information or knowledge that we are unaware of or are biased towards, also known as tacit or biased knowledge.

- Unknown-Unknowns: Information or knowledge gaps or risks that we are unaware of.

One important aspect of the matrix is that it is driven by perspective and experience. What is known to me might not be known to you in various ways.

Known-Knowns

Known-Knowns are the straight facts — the truth. These could be laws, laws of physics, first principles, or simple, basic facts backed by evidence. We know that the sun produces light, and the Earth orbits around the sun because of gravity.

But how do we know that we know something? We know that we know something by validating it or gathering evidence — if something cannot be proven or has no evidence, it is not a known fact.

Applications to Strategy

Review what you know about a strategic decision and pressure-test your knowledge—what is an actually provable fact, or what is an assumption or belief hiding as a fact? Unquestioned assumptions can be dangerous to your decision. Assumptions are beliefs without proof—our unproven expectations about the future. Since assumptions are unproven, they inherently contain uncertainty or risk and thus, should be treated as Known-Unknowns. For what do we have evidence, and what do we not have evidence? If a statement is not provable or has no evidence, then it is a Known-Unknown.

Collaboration is an important part of this review process. Is there something your superior might have said and taken for granted but you think lacks concrete evidence? The framework and process should give you leeway to question or review information about a topic—"blame" the process if you feel uncomfortable asking a co-worker or superior for evidence.

Finally, an important part of this exercise is to decide which Known-Knowns are relevant to the situation. A statement like "the sky is blue" is not relevant to making a decision on whether the United States should invade Vietnam, but "an upcoming, long rainy season" might be. You be the judge. Put facts of questionable relevance off to the side in a "parking lot," a place for ideas to be followed up on later, as you learn more, or for feedback from a collaborator/superior.

Known-Unknowns

Known-Unknowns are identified risks—uncertain outcomes of future events, information gaps, or important questions that affect our strategic decision to which we don't have answers. For example, we don't know if the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates at the next Federal Open Market Committee ("FOMC") meeting, but we know it is something that the FOMC is considering and is an option they can pursue. This is a future, unknown event that we have no way of accurately predicting.

Perspective and specifics matter here. For example, a startup developing a next-generation disruptive product in their garage (e.g., Google circa 1996) an Unknown-Unknown or a Known-Unknown to an incumbent competitor (e.g., Yahoo!). But, Google is obviously a Known-Known to the startup's founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin. Yahoo CEO Tim Koogle might believe or assume that startups are entering his space, which would be a good operating assumption for any CEO to make, and this assumption would be a Known-Unknown. New competitors are something Tim has a general awareness of and knows their potential risks but lacks information on who, what, or where. If Tim had no idea that there were potentially superior search algorithms, then Google's emergence to him would come from the Unknown-Unknown.

Applications to Strategy

As a decision-maker, you should spend the majority of your time gathering as much high-quality information about the highest impact Known-Unknowns in order to make them Known-Knowns.

Once you have identified all of your Known-Unknowns for an important decision:

- Map or visualize your Known-Unknowns to your strategic decision to identify (a) any natural groups or categories through affinity mapping and (b) any major dependencies to your decision. A decision tree can help here, too.

- Prioritize your Known-Unknowns by the highest impact on the strategic decision.

- Develop a research plan to learn more about your high-impact, Know-Unknowns.

How do you determine what is a high impact Known-Unknown? If an outcome or range of outcomes from a Known-Unknown completely alters your decision, its higher impact. If it only slightly changes your decision, it's a lower impact.

What if you don't have time or resources to investigate? Unfortunately, this will often likely be the case. Make sure you explicitly communicate the risks or gaps associated with the decision. Consider developing criteria for when to change course or contingency plans for the Known-Unknowns, if possible.

Unknown-Knowns

Logically, the simplest definition of Unknown-Knowns is things that we don't know that we know. How do we not know things that we know? I suggest two ways to break this concept down.

The first category of Unknown-Knowns is tacit knowledge — knowledge that is difficult to express or extract, and thus, is more difficult to share through writing or verbalizing, and often includes wisdom, experience, insight, and intuition. Tacit knowledge is often referred to as your gut or intuition talking to you.

Tacit knowledge is prevalent in organizations, and important information about a topic might not be available to someone when they need it. The Department of Defense knows about this all too well. In 2008, a B-2 Bomber, "the Spirit of Kansas," took off for a training flight in Guam. Seventeen seconds after takeoff, the pilots lost control, ejected, and the $1.4 billion bomber crashed and was completely destroyed. NASA performed a root cause analysis and published a case study on this B-2 mishap. What was the ultimate cause?

In NASA's climate of daring enterprise and unparalleled innovation, our efforts can be foiled by the challenge of simple communication... the Department of Defense lost a $1.4 billion aircraft because one maintenance technician working on the aircraft was not aware of a workaround developed in the field. In NASA's climate of daring enterprise and unparalleled innovation, our efforts can be foiled by the challenge of simple communicationIn NASA's climate of daring enterprise and unparalleled innovation, our efforts can be foiled by the challenge of simple communication. (Emphasis added).

In other words, undocumented tacit knowledge.

The second category of Unknown-Knowns is what I called "biased knowledge." Dr. Herb Lin, a senior research scholar for cyber policy at Stanford University, explains this concept well:

Logic would suggest it is something that is “known” in some sense of that term, but that is, for all practical purposes, unknown at the time that it is needed. Things once known but now forgotten, things known but deliberately ignored, things that are known but that people wish were not true, and things once seen as scary, but no longer seen as such, all might qualify as unknown known...

To broaden the scope—concepts like laziness, willful ignorance, arrogance, and other cognitive biases that inhibit our ability to recall or know something. For example, I might know that I have information relevant to a decision in my email archive—something that is a Known-Known—but I'm feeling lazy, or get distracted or forget to search my email, and consequently, it remains unknown.

There is also an organizational dimension to "biased knowledge." An organization might have information that is purposely ignored, denied, or dismissed because it is taboo, disagreeable, or intolerable to the organization's culture.

Applications to Strategy

How do we make key Unknown-Knowns, known? This aren't many effective ways to do this in the short term. Longer-term, it will take new habits and processes.

A web search will yield many ways to improve your self-awareness. Try sleeping on a decision. Maybe it's time to listen to your intuition or your gut—what does it tell you about a decision? Does the thought of one approach immediately give you the chills? There's likely something to explore there.

From an organizational viewpoint - how can you counteract or mitigate your or your organization's behavioral biases? NASA recommends establishing formal documentation and knowledge transfer processes, especially for critical path activities and teams.

we need to ensure designers pass on their knowledge to their successors and leave detailed documentation for future personnel.

Formal mentorship, networking, and training programs will help ensure information is transferred. Finally, establishing a culture that values open communication will help ensure tacit knowledge is shared.

Unknown-Unknowns

Unknown-Unknowns are a similarly difficult concept to grok. Unknown-Unknowns are completely unexpected or unforeseeable conditions or events, risks we cannot imagine, or are simply factors of whose existence we are unaware. Military strategists often refer to these types of unknowns as the "fog of war." The moment an Unknown-Unknown becomes Known, it usually generates surprise, bewilderment, or amazement.

Perspective matters here again. For a silly example, did you know that there are professional surfing dog schools? Neither did I, and never would have thought it was possible. Until this Unknown-Unknown just became Known, my dog, Max, would never have been able to catch a wave.

One interesting aspect of Unknown-Unknowns is that they are driven by perspective and, as such, are specific to a person, team, or entity. In 1979, a young Steve Jobs visited Xerox Parc, Xerox's legendary innovation lab. Xerox Parc had built early prototypes of a computer "mouse" and "graphical user interface" to work in conjunction with the computer "mouse," both of which have been used in computing for decades. These prototypes were Known-Knowns to Xerox; they had been working on them for years. But to Jobs—the CEO of one the hottest tech firms in the Silicon Valley—they were both Unknown-Unknowns. He had no idea this was even possible. His reaction after seeing Xerox's mouse and associated user interface was amazement, and proclaimed, ‘Why aren’t you doing anything with this? This is the greatest thing. This is revolutionary!’

Applications to Strategy

How do we learn about what we aren't aware of? It's not easy, but by exploring, researching, and prototyping, you have a shot.

To explore, as Steve Blank would say, get out of the building! Talk with customers, friends, or co-workers about your decision domain. Find an expert in your decision domain and pick their brain, or find a trusted confidant to bounce some ideas around. Conducting a series of exploratory interviews or focus groups of those that might be affected by our decision to uncover something relevant to the decision that you've never considered. I've never spoken with a customer and not learned something new. Exploring is precisely what Jobs did when he toured Xerox Parc, and the rest is history.

Rapid prototyping is another great way to quickly learn about a topic. In software engineering, spikes or tracer bullets are fast prototypes of barely functioning code that developers use to understand what problems they might encounter before actually building something. Think about what quick prototypes or tests you can conduct to learn more about your decision area.

This will be difficult to do in resource or time-constrained environments, but for the most important of decisions, consider taking some time to explore your decision domain.

Takeaways

Information is always incomplete in uncertain environments, and the Known-Unknown Matrix is a framework that helps with strategic decisions. The matrix helps to sharpen your thinking and untangle facts from fiction. I've also found it to help with "writer's block" and to organize my thoughts on a strategy decision. Curiosity and ego-less analysis will be your friends — question and validate what you know about the situation. Prioritize any knowledge gaps and attempt to fill them. Explore your decision domain to uncover new information. And as Joel Embid says, trust the process.